Ever since humans have been humans we’ve dreamt of flying. But what’s the appeal of travelling skywards?

As far back as historical records go, there’s evidence of mankind’s urge to fly. Some of the most ancient stories have flight as a central motif. A legend from Sumer, one of the three oldest known civilisations, tells of a king called Etana who saves an eagle from starving; in return the eagle carries him far into the air to the ‘plant of birth’, the key to fertility.

Much later we have the myth of Icarus and his father Daedelus, who fashioned wings from feathers and wax to escape the labyrinth. The escape was successful, but in sheer exhilaration Icarus flew too near the sun, the wax melted and he fell into the sea.

Up to the spirit in the sky

Throughout the ages a host of deities and heroes we have imagined, painted and sculpted have defied gravity – Nike, Hermes, Gardua, Valentine’s card cherubs, angels, Superman … if they can fly, why shouldn’t we?

This longing to fly is often expressed in dreams. Dreams of flight appear in numerous cultures as a thrilling liberation from the ground.

Travelling skywards in dreams and visions, of course, wasn’t enough. People wanted to do it for real. In the First Century AD, the Chinese emperor Wang Mang arranged for a man to be covered in feathers who, we’re told, then glided 100 metres. Many other less successful (and probably more factually accurate) attempts followed. In the 9th century, the Andalusian inventor Abbas ibn Firnas made wings from wood and silk and jumped from a promontory. He didn’t die, but a witness tells us that ‘his back was very much hurt’. Ouch.

From magical to mechanical

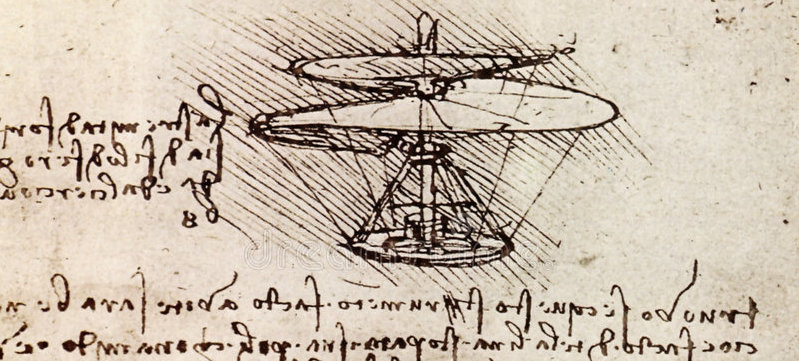

Leonardo Da Vinci gave new form to this apparently universal human compulsion to fly. The Renaissance inventor obsessively sketched designs for all kinds of flying devices including gliders, hang gliders, parachutes and something like a helicopter.

Balloons became the first reliable means of heavier-than-air flight until, through dedication and bravery, the Wright brothers achieved winged flight. This led to the century of Earth and space flight, landing men on the Moon. Inter-planetary prospects are developing fast.

Today there’s a staggering variety of ways to fly recreationally. You can parachute, hot air balloon, hang glide, paraglide. You can even take your life in your hands, dress in a wingsuit, and leap from a mountain: Wang Mang would have loved that.

So why fly?

But why this urge to go heavenwards? Ethnologists Thomas Hauschild and Britta N Heinrich argue that the desire to fly is a universal trait based on our ability to walk upright, our sense of balance and our ability to construct a bird’s-eye view of ourselves and the landscape around us. It’s hardwired in us.

Surely it represents the breaking of earthly restraints. It means release. It means freedom. And it means more than this – more than merely escape. Throughout myth, religion and language (‘lofty thoughts’, ‘higher purposes’), travelling skywards is a search for greater understanding, for reflection and for transcendence.

Today, flight can be merely a practical function that takes us somewhere fast, or an adrenaline-fuelled pursuit of exhilaration – the Icarus approach, if you like. But there is still room for the transcendent.

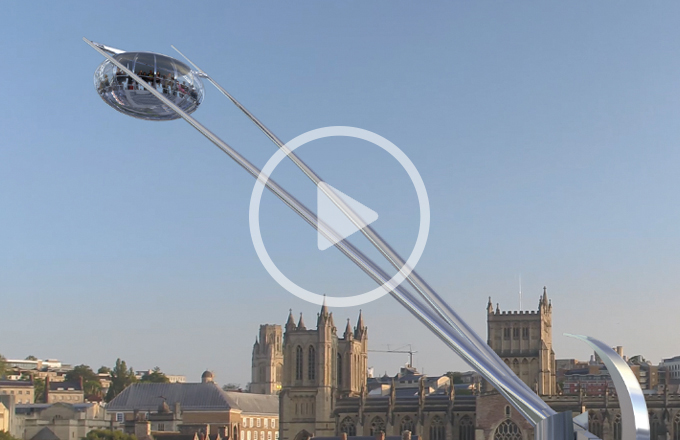

For Arc, flight is indeed exhilarating, but it promises more than that. It represents liberation from solid ground; an opportunity to contemplate the world from above and understand the landscape below.

Arc, unlike any other means of flying, is silent, calm, magically serene. It offers an archetypal experience of ascending. Maybe not quite to heaven, but certainly to a higher plane.

Nick Stubbs is the inventor of Arc. An architect and chartered environmentalist he is passionate about sustainability and projects that offer practical real-world solutions to global challenges.

Nick Stubbs is the inventor of Arc. An architect and chartered environmentalist he is passionate about sustainability and projects that offer practical real-world solutions to global challenges.

Nick Stubbs is the inventor of Arc. An architect and chartered environmentalist he is passionate about sustainability and projects that offer practical real-world solutions to global challenges.