We’re hooked on grandeur. A mountain range, a rock anthem, a night sky, a Monet landscape ... they all have the capacity to fascinate us, lift us and humble us in equal measure.

But grandeur isn’t reserved for the ethereal or intangible, for nature, art or music. Architecture also inspires us, subtly influencing how we think and quietly impelling us to act in certain ways. When Churchill said, ‘we shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us’, he was referring to the design of a historic workspace, the Commons. He'd observed how its layout enabled the occupants to debate in a more adversarial way – reinforcing the particular cut-and-thrust style of governance he approved of.

For the most part though, a historic environment affects our behaviour in a more gracious way – like inspiring us to take some time out to explore a new ‘old’ city.

The idea of connecting with the Old World is an attractive one, and each year, millions of visitors flock to heritage locations. It’s not just the aesthetic of towering spires or crumbling stucco which draws them. Human beings derive reassurance and security from being in the presence of venerable architecture, all the more so amidst societal turbulence and global change. We miss it the moment it's gone. Beautiful buildings link us with a time we can fancifully imagine to be slower, more measured and more sublime. The architecture that outlives such periods seems to speak a language of stability and continuity. Its value to us transcends that of bricks and mortar – for a moment, we can pause, breathe, and be shaped by it.

Could buildings better our lives?

The Victorians believed that exposure to culture in any form improved people, and made them ‘more moral’. It’s easy to dismiss this as naïve, but there is an undeniable connection between the perception of beauty and behaviour – in 2014, Historic England reported how ‘life-satisfaction’ and wellbeing increases for those who take the time to visit heritage sites, more so even than sports and the arts. In the same study, historic towns and historic buildings were considered to possess a sense of ‘longevity’ and ‘grandeur’; qualities perceived to be absent from their modern counterparts. Some studies (3.1) on cultural attendance have even suggested it might result in a longer lifespan.

The Victorians believed that exposure to culture in any form improved people, and made them ‘more moral’. It’s easy to dismiss this as naïve, but there is an undeniable connection between the perception of beauty and behaviour – in 2014, Historic England reported how ‘life-satisfaction’ and wellbeing increases for those who take the time to visit heritage sites, more so even than sports and the arts. In the same study, historic towns and historic buildings were considered to possess a sense of ‘longevity’ and ‘grandeur’; qualities perceived to be absent from their modern counterparts. Some studies (3.1) on cultural attendance have even suggested it might result in a longer lifespan.

In that same year there were around 67 million visits to heritage sites in England. So what if you could convert those visits to life-satisfaction and measure the effect?

Heritage-watching is not a fad. Way back in 2001, MORI’s survey for English Heritage (1.1) found that 81% of people said they were interested in how the built environment looks and feels, and one-third ‘very interested’. More recently, 63% of respondents to research commissioned by the BBC said they believed that the UK did not do enough to look after historic buildings; and three-quarters were concerned about the loss of historic buildings. It seems that it is important to us that we not only retain and care for, but continue to develop our relationship with historic cities and locations. And finding new ways to look at them is a key part of achieving that.

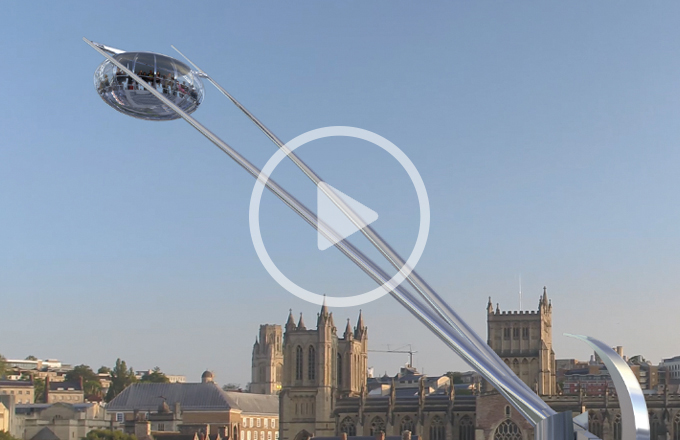

This, of course, is the purpose of Arc. We envisioned not a ride, but a voyage which would shape and connect people: with each other and with the historic locations they were viewing. But our aim was also to lift them – figuratively and literally - and to help them see the grandeur in those locations with fresh eyes.

Several years on, that mission seems more poignant and appropriate than when we began. In an increasingly sombre, fragmented and seemingly fragile world it’s easy to forget the beauty and stability that exists all around us. We need to continually look for that grandeur in all things, including our cityscapes and built environments. ‘Life is short, art is long’, wrote Hippocrates. Keeping our focus on ‘the long game’ – that of mankind’s past achievements and future possibilities – may just give us some hope of better.